Ghost Recon: Wildlands is the most pure and refined two-player video game we’ve ever played. It’s fitting that the game’s subject matter is cocaine—playing is a chemical-like experience where you’re locked into each moment, and clearing your head as the future unfolds is a struggle. Focus. That’s what Wildlands demands of its players, and the simple harmony of the game’s tools and design makes it achievable.

Game time in Wildlands contrasts so starkly with other games that comparisons are comical. I was reminded of Monster Hunter: World. One minute you’d be chasing the hellish fiend Vaal Hazak, ducking out of the way of his enormous sewage novas, sweating and gobbling nulberries as you climb piles of rotting corpses, looking for an opening while his tail whips around; and then the fight would end, and you’d retreat to your character’s quarters, into the arms of your adorable cat-like companion, the Palico. You’d spend a few minutes toggling icons to send your Palico on an expedition to gather materials. You’d watch him loll about your room amidst the delightful creatures and plants you’d collected across the world, and then head out to harvest some botanical herbs and check whether the merchants were in port. If you were serious about the game, you’d also spend fifteen minutes shuffling your gear to take advantage of your next opponent’s weakness.

You won’t find these tranquil inactivities in Wildlands. While the game is running, from one moment to the next, all you’re thinking about is your position, the enemy’s position, and what tools you might use in the next instant to take advantage of the situation or compensate for the mistake you made the moment before. There are no distractions: no health or stamina bars, no corpses to loot, no explosion of items to examine. How can a game without these complications require more focus than a game that includes them?

Without a mess of information that requires constant monitoring, only the action—the enemies and our shots—absorbs us. The action in Wildlands is so fast and complex that it regularly used up our attention spans. The two of us playing together could only play for roughly two and a half hours at a time. After that, carelessness, inattentiveness, and imprecision grew too much to continue. However, the joy of being totally locked-in every time we turned on the game never diminished. Wildlands made it tough to want to vegetate on another game’s mobs again.

Walking the Tightrope Between Desire and Ability

In Ghost Recon: Wildlands you play as a Ghost, a Special Operations soldier on a black op in Bolivia. Your mission is to sabotage Santa Blanca, the militarized local cartel that controls the entire country’s cocaine manufacturing and distribution. When you boot up the game, you’re dropped at a neutral rally point. The whole map of Bolivia, divided into regions with separate difficulty levels, is open for exploration. You choose a vehicle. Helicopters, dirt bikes, rusted pick-up trucks, armored vehicles, and biplanes are available in abundance. You climb inside, put the pedal to the metal, and race into the parched mountains to bust up an enemy compound or shake down an informant.

Wildlands’ tools are fairly standard: three guns; several varieties of explosives; night and thermal vision; and a drone with explosive, healing, electronics-disabling, and enemy-ID functions. Players also have access to a band of NPC “rebels” who can fight by their side or perform functions such as marking enemies, dropping mortars, delivering vehicles, and creating a distraction. (We played the entire game together in co-op, so we were not able to use Sync Shot, the mechanic single-Wildlands-players use to shoot enemies in tandem with their AI teammates. This article excludes discussion of Sync Shot.)

Wildlands doesn’t care what tools or methodology you use to accomplish your mission. Objectives are incredibly simple, summarized in just one phrase, e.g. “Hack the terminal” or “Interrogate the Sicario.” Every enemy in the game, whether he’s a cartel boss or a flunky, will die to a headshot. You might drive an armored vehicle directly into a compound while your teammate uses its mounted machine gun to blow enemies away. You can methodically stalk the perimeter, quietly killing every guard, disabling the compound’s generators and alarm system, and then waltz to the objective. Sending large groups of rebels into the teeth of the enemy, dropping mortars on the ruckus, and sniping from hundreds of meters away can work, too.

To an outside observer, every Wildlands mission looks much the same. Each compound is similarly organized—snipers at the towers, guards at the gate, and enemies relaxing at kitchen tables inside muddy adobo buildings or having a smoke in the shade outside. The same five mission types—with the exact same objective—are repeated in every map area. Differences in the landscape, such as the endless bleached expanse of the salt flats, the flutter of pink wings at the flamingo pool, the occasional underground tunnel, and the swanky beachside pad of a wealthy cartel member, provide good-looking, diverse backdrops, but I can’t say that they much change the basic mission gameplay.

That’s okay. The fun in the game comes from the tension of balance. When you’ve got a helicopter, tons of explosives, and a small army of followers, you’re a militant dynamo. It’s easy to be a God of destruction and chaos. Crashing your helicopter before you reach the mission, causing a nine-car pileup that immolates 20 civilians on the highway, blowing up the plane you were supposed to steal, nuking the supplies you were supposed to protect, and engaging in a loud firefight and drawing twenty cars packed with enemy reinforcements—this is a piece of cake (and a lot of fun, too). But it is the game’s failure mode. Being a ghost—unseen and unheard—is difficult. The patience and diligence reconnaissance requires is difficult. Doing adequate reconnaissance, forming a tactical strategy, and then seeing it through, as an unseen and unheard ghost, is the most challenging feat of all.

This is the higher calling of Ghost Recon: Wildlands and the reason completing identical missions never seems to get old. You struggle to maintain your balance in the face of overwhelming temptation—the temptation to continue shooting once you’ve already missed and your position is known; the temptation to blast a supply truck with the grenade launcher until it stops moving, the temptation to advance into a compound past your cover despite not knowing the enemy’s precise location. Balance is personalized. A player who is a master of his SMG might be able to take down five enemies that surprised him with five perfect, consecutive headshots; a guy with a wobbly thumb had better keep out of the compound unless he has every baddie marked. As the game difficulty increases, and every enemy becomes smart, mobile, and eminently lethal, you feel your balance shift. The quality of your decisions and precision of your aim determines the parameters of your behavior.

From Irrational Decisions to Realistic Tactical Maneuvers in a Steady Progression

That Wildlands is a tactical game—not a shoot ‘em up—is immediately apparent. One of our first missions was to interrogate an enemy; when he fired a few shots in our direction, Genevieve unceremoniously gunned him down. Mission failed. You have to think about how to approach an enemy you don’t wish to kill, but who has the power to kill you. Next we attempted a mission that required defending a radio. Carloads of enemies arrived and parked off the road, surrounding the radio and pouring on us from all directions. Cowering inside a building, we took pot shots and killed a handful before they burst through the doors and put a merciful end to our toons. The radio had long been destroyed.

We died and failed the “Defend the Radio” mission at least ten times before we realized that we weren’t meant to gun down every enemy in this particular mob. We couldn’t succeed by waiting inside a building for our executioners to arrive. In order to protect an asset from more than 30 armed, mobile, and intelligent enemies, a group of two has to think and plan. We littered the town with explosives and parked a few cars on the road to block enemy access to the radio and our stronghold. Suddenly the mission was completable.

If, after failing “Defend the Radio” so many times, somebody had pointed out that we were playing Wildlands on dog-easy Regular mode, we might have lost hope for competing at the higher levels. Luckily the game has a beautifully designed progression curve. The process of improving at Wildlands isn’t a matter of taking on bigger mobs, altering your loadout or gear, or buffing your damage. Leveling up, you don’t simply get stronger guns or more powerful explosives. Rather, your ability to influence and control the battlefield—to deal with the game’s challenges—increases. Your tools become more serviceable, with new functionality, increased quantities, and shortened cooldowns. Select physical attributes, such as stamina and stealthiness, increase as well. Your footsteps get quieter; your drone identifies enemies quicker. “Defend the Radio” was never any simpler than it was the first time we attempted it. It certainly never became a slam-dunk win. Our skill at utilizing the game’s tools simply increased.

Each map gets a difficulty rating from one to five. In beginner maps, enemy encampments are rudimentary and understaffed. Cartel members doze and stand around campfires, rarely calling for backup or even so much as moving when under fire. You’re taking on amateurs. And, when you’re fresh, new, and green, you can absorb several seconds worth of machine gun fire, or a couple hard sniper bullets.

Players fight the Santa Blanca cartel, but throughout the game, they’re harassed and bedeviled by Unidad, Bolivia’s military force. These tough, aggressive enemies will spot you anywhere on the map, whether you’re traveling or stationed outside a Santa Blanca base, and call reinforcements. Like the police in Grand Theft Auto, infinite Unidad armored vehicles and helicopters will arrive unless you flee or dispense of the original agents before they’re able to radio for backup.

Ability to deal with Unidad reinforcements is a litmus test of improving at Wildlands. At first, any and all Unidad soldiers must be avoided. As you improve, you find yourself blowing up several rounds of reinforcements before finally succumbing. Then you start to live through most Unidad encounters, with hundreds of enemies killed and a boatload of XP to show for it.

As the map’s star ratings increase, missions include raiding Unidad bases, and what were once small-time Santa Blanca camps are now enormous compounds, outfitted with machine guns and alarms. Guards are posted in every tower and on every wall. Enemies quickly call for reinforcements, which arrive in baddie-packed pickup trucks, APCs, or helicopters. Your foes become mobile; they listen for your gun-fire and try flanking maneuvers. Even the topography becomes more difficult to navigate—most bases in five-star zones are difficult or impossible to access as an intruder, situated on high elevations with only one or two monitored points of entry. It takes real thought and planning, along with a heaping dose of skill and luck, to infiltrate one of these places.

Then Tier Mode arrives. Shortly after activating Tier Mode and getting into Advanced difficulty, we reached Extreme difficulty. The difference between Tier Mode, in Advanced or Extreme, and Standard is so stark it’s hilarious, but you’re ready for the challenge now that you’ve mastered most of the game’s tools. Still, Tier Mode is ass-scorchingly difficult. If you’d been playing a Special Ops soldier taking down gang-men and their hired help for the majority of the game, now it feels like you’re the local yokel goofing off with a plinky pistol in the mountains; and hundreds of highly trained, highly skilled Special Ops soldiers have been tasked with the mission of finding and annihilating you. They’re ready to take you down the second they smell you, and a single bullet is enough. The game becomes, in a word, realistic. Staying alive is a tricky proposition, achievable only with extreme caution and discretion.

The presence of enemies is no longer telegraphed by a smear of color on the minimap. If you neglect to find and mark every last enemy beforehand and formulate a plan of attack, the simple act of walking near an enemy encampment spells instant death. A momentary mental lapse, or having a bit too much faith in a piece of cover, gets you killed before you realize what happened. Being spotted by an enemy in the corner of your frame, and not taking immediate action to move away or reorient your character, is the same as throwing a grenade at your feet. Vehicles full of machine-gunners fly along roadways and kill you from 90 meters away before you have time to turn your camera. If a single enemy approaches your group from behind, and nobody notices, the entire group will likely perish.

One-on-one gunfights are fifty-fifty affairs—most times your odds are worse than that. If you confront an enemy in a corridor and miss your first shot, his is going to land. You’ll die. He’s a more skilled marksman than you. Enemy AI is so strong—their aim so precise, their line-of-sight so ideal, their movements so intelligent—that being a human player seems a bitter, unfortunate handicap. Calling for rebel backup once seemed like cheesing the game; now you need raw numbers on your side to have a chance against superior firepower and coordination.

Wildlands in Tier Mode is probably the most difficult game we’ve ever played, but we continued playing. We continued having fun every night. We beat the game at around Tier 20, without quite making it to Tier 1 (Tier Mode counts down from 50, with Tier 1 being the highest level), and we were disappointed that the game was over. We wanted to keep playing, and keep advancing.

Perhaps part of the magic is that Wildlands continues to be enjoyable even as you fail. Mistakes are often obvious, outrageous, and funny to watch. When you land your helicopter on the roof of a building, jump out, and expect to be able to interrogate an enemy with his posse surrounding him, you can only shrug as you’re gunned down from all sides. When you lose a 1v1 with a NPC, you can’t help but laugh at yourself. When you accidentally blast your group with the grenade launcher, it’s hard to be butt-hurt. Failure in some games is confusing and noxious—decision-making, resource management, timing, groupmates, cooldowns, and unlucky enemy AI work together in a swirling, unhappy miasma to cost you a mission. In Wildlands, when you stand up from cover and shuffle your weapons in full view of three snipers, you’re a simple idiot. Mistakes are so plain and crystal-clear that occasionally one of us would see the other’s position, and, knowing their death was imminent, open the menu to equip the Medic Drone in advance.

When we both died, we respawned directly outside the selected mission, ready to try again. No XP penalty, no enormous travel-time setback, no permanent forfeiture of some element of the mission. It should be mentioned that once you boot up Wildlands, death is the only time you’re forced to wait through a load screen. It feels like the perfect penalty. Playing Wildlands, you crave its uninterrupted play time, the perfect loop of traveling to a mission, finishing it, and returning to the same helicopter to float to another mission. In games like Warframe, load screens are a pre-set barrier, a hurdle you must pass again and again, several times per hour, just to get to play. The grim churning of the Playstation load screen in Wildlands is a sad reminder of your failures, and you’d better use the time to examine your mistakes and form a new plan.

Liberated Gameplay: Fast, Efficient Completion And Headache-Free Loot

When you venture into a new region in Wildlands, missions aren’t marked, but several types of intel are. There’s main quest intel, which reveals details about the region’s boss and the next step for locating and defeating him. A handful of gang leaders rove the map—these targets must be captured and interrogated to divulge the locations of weapon crates, skill points, and bonus medals, which boost the rank of a skill category without requiring the player to spend his own points and materials. The last type of intel marks the locations of rebel ops, missions that buff your rebel army’s abilities.

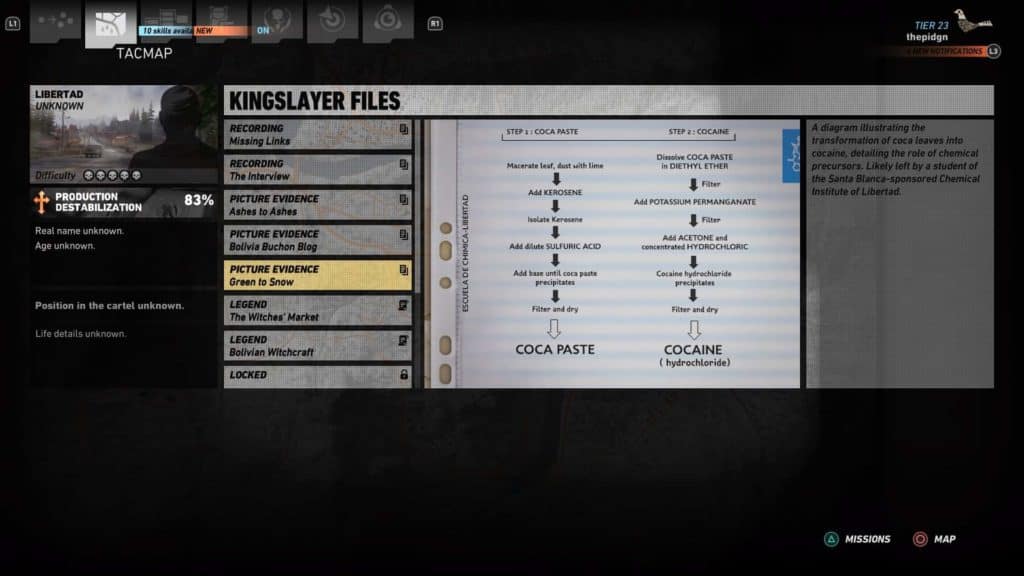

Gathering all three types of intel marks the locations of every item to collect and mission to complete in that part of Bolivia, with the exception of “Kingslayer Files,” textual artifacts that appear on the map only when the player is nearby. Players are free to choose their activities and order of operations. Usually we’d travel from one mission to the next nearest item or mission. We almost never fast-traveled to a rally point—there was no need. Objectives were close enough that a typical trip was no more than 3 km. If we’d been beating on the doors of a particularly tough compound and failing repeatedly, we’d hop in the helicopter and collect a few easy, feel-good skill points or Kingslayer Files nearby before returning to the meat grinder.

This mission arrangement—every mission marked on the map, with missions of different types no more than 3 km away from each other—seems vanilla and sensible. We didn’t think about it much as we played, and we certainly weren’t going to devote space to explaining it in this article, until we played Narco Road, one of Wildland’s DLCs. In a new area of Narco Road, only rebel ops and the main mission are marked. In order to reveal skill points and weapon crates, you must complete rebel ops (and perform car stunts) until you earn a critical mass of “followers,” at which point somebody volunteers information.

Rebel ops and main mission quests in Narco Road were as many as 7 k.m. away from each other. That’s two or three hard, real-life minutes of travel in a helicopter—many more if you drive Bolivia’s winding mountain roads. In the game, it feels like 15 minutes. You’re tempted to get up to take a piss. You had to complete the same missions type on repeat with interminable travel between each—and then, once the weapon goodies were revealed, they were just inconveniences, scattered 7 km away from each other across a map you’d already crawled fifteen times. The process of clearing a region was exhausting and irritating. It took at least twice as long as it did in Wildlands. We quickly tired of Narco Road. Seeing the way a seemingly trivial change threw the speed and harmony of the gameplay out of whack made us appreciate how finely tuned Wildlands’ format is.

Wildlands doesn’t try to set players’ schedules, nor does it coerce us into playing certain content with promises of riches or, worse yet, the chance at riches. The weapon that any given crate contains is listed, free to see when you toggle over the crate’s icon. Bonus medal types are marked, too. You don’t have to bust your ass for something you don’t want. Instead, you decide in advance.

The main loot in Wildlands consists of “supplies.” There are four types: gasoline, food, medication, and coms tools. These supplies are consumed in tandem with skill points to level abilities up, and, in Tier mode, to increase your weapon’s damage. Some types of missions provide large quantities of supplies as completion rewards, but individual crates are also found in any inhabitable area of the game, friendly or hostile. Tagging a single crate awards the player a variable quantity of its supplies. In the lower levels of the game, players receive between 50 and 500 supplies per crate; in Tier Mode, the maximum increases to more than a thousand.

When we looted our first supplies in Wildlands, we were delighted to see that rewards were shared with the group. That joy was dampered when we received a paltry 50 or 100 coms tools. A meagre quantity like this couldn’t make much difference in our skill progression, we figured. Having recently acquired a heavy distaste for looting (see Fallout Made Me Hate Looting), we were happy to ignore and avoid the insignificant crates.

That feeling changed as the game progressed. When we really wanted to buff a certain skill or attribute, we become desperate for even a paltry quantity of the necessary supplies. Then, in Tier Mode, changing to a new weapon meant upgrading it from scratch; it took numerous upgrades for any given weapon to be able to one-shot an Unidad soldier. After completing missions, we began using the sniper rifle’s scope to canvass our immediate area. “Zooming in” with the scope revealed supplies on the minimap that were up to 40 meters away. This mini-game, if you could call it that, became a relaxing, triumphal part of clearing an enormous compound.

In most games, opening loot is like getting the mail. There could be something great in there! Your tax refund. A check from the Subway class action lawsuit for printing the expiration date of your credit card on the receipt. Usually there’s nothing great in today’s mail, but you won’t know that for sure until you open everything. And after you open it, even if there’s nothing important, you have to deal with it. You have to shred the mail that contains your financially identifying information. You have to dump a pile of catalogues in the trash. Most days of the year, the act of dealing with the mail is simply a headache and time-suck.

Supply “loot” in Wildlands is a constant. It’s always the same thing, in the same places, with the same function. It’s more like a simple form of currency—think loose change in the couch—than a sealed envelope. If you’re cleaning and you happen to find 5 bucks, it’s a pleasant surprise, not enough for lunch, but maybe enough for coffee. If you ordered delivery food and forgot to add a credit card tip, digging through the sofa cushions and the pockets of jeans in the laundry becomes your salvation; will you find five bucks to give the driver, or just a few crusty, shameful pennies? The supply system in Wildlands is perfect because its rewards are optional, useful, fair, consistent, and abundant—all at once.

Creative Content and Concert-Quality Soundtrack

We played the entirety of Ghost Recon: Wildlands with Spanish-language audio and English subtitles. Hearing the game in Spanish electrified the action and added some kind of authenticity to the game. The Spanish voice actors seemed enormously better than the English voice actors. Watching the English-language videos and gameplay on Youtube, dialogue seems stilted and corny—funny at best, but certainly not as vivid and intense as the Spanish version.

We were tempted to believe that we were simply biased toward the Spanish-language version because it was exotic to us, but that’s probably not the case. We hear Spanish spoken every day in our neighborhood and have Spanish-speaking friends and coworkers. When we turned on Crew 2’s Spanish-language audio, it was abominable, with a corny, loud, lisping announcer-style voice actor. The Spanish voice acting didn’t even seem as good in Narco Road, Ghost Recon: Wildlands’ DLC content, as it did in Wildlands itself. If you know even a little Spanish, or if you usually find the voice acting annoying in games, we highly recommend turning on Spanish-language audio in Wildlands. And if you’re a native Spanish speaker, let us know in the comments what you think of the Spanish voice acting in Wildlands. Is it just as bad as the English, and we’re just ignorant gringos?

The story itself probably didn’t win any awards—there isn’t a single narrative moment or character that would stick out if you’ve read a few Daily Mail articles about El Chapo. There’s even a mustached General Baro who’s a dead-ringer for almost every corrupt Latin American dictator you could think of. Fighting the war on drugs in a South or Central American country is probably a harder sell in 2019, as cannabis is legalized across the U.S., than it was at the time of the game’s release in 2017. Despite the story’s stereotypical premise and assumptions, it wouldn’t be going too far to say that we engaged with the text documents and videos in Ghost Recon: Wildlands more than in almost any other game we’ve played. Many were interesting or arresting—we didn’t automatically skip them. We began to despise our sharp-tongued boss, Karen Bowman, after watching her force a cartel boss to snort several ounces of cocaine. We laughed when they mentioned that some guy was the cartel’s “cocaine quality tester,” and were notably disgusted by the boss whose job it was to dissolve people’s bodies in 55-gallon drums of chemicals. The world of the game’s story is expansive and beautifully developed; if you dig in, you’re sure to find something interesting, from the way cocoa picker’s hands turn yellow to a cocaine purification recipe.

Before playing Wildlands, we habitually muted game music and blasted Spotify playlists instead. Even if it meant dying to a few audible attacks, it was worth it to not have to listen to the sound. Usually there’s a cheesy background melody that may or may not morph into a thumping combat track, a few battlecries and sound effects when you use a skill, and the occasional grunting of a monster or beast. We recently booted up Black Desert, and the sound was unbearable: the fantasy genre’s orchestral sludge of cheerful flute solos, windy strings rising to a crescendo, and the beat of the sinister snare drum.

In Wildlands, there are layers upon layers of sound. Insects chirp and buzz; birds sing; cars rumble on asphalt and helicopters whirr in the distance; there’s constant chatter on your radio, whether impassioned cries or shouted orders. While you’re fighting, the rattle of gunfire and punctuation of explosions saturate the air. We turned off Spotify the first night we played, when we drove our first car in the game and noticed that we liked the music on the radio, cheeky traditional Bolivian tunes, such as this trumpet song. We kept Spotify off.

One night, we left the game running and went to the kitchen to make a snack; hearing Wildlands music in the background, we couldn’t believe that sound was coming from a video game. The soft, twangly guitar, driven, distorted guitar, and hard-driving drums seemed like the enigmatic soundtrack of Grizzly Man, or something you’d hear at a concert of an indie composer such as Ryan Brown. It seemed like there had to be a real musician behind the soundtrack of Wildlands.

We did some Googling and discovered that musician is Alain Johannes. He’s an accomplished Chilean-American producer and multi-instrumentalist who has played with Queens of the Stone Age and Chris Cornell. We at Co-op Gaming Dot Info want to offer a huge thanks to him, the music supervisor, audio director, and others at Ubisoft who worked on Wildlands’ sound for making the first video game we thought was worth hearing. We hope the soundtrack of Ghost Recon: Breakpoint has as much love and dedication as that of Wildlands; we’ll appreciate it if it does. You can hear some of the music from Wildlands and learn more about the making of its soundtrack in this video: