Browsing for books about video games on Amazon, I didn’t find many options. Death by Video Game: Tales of Obsession from the Virtual Frontline was easily the most sensationalist title. Its description reads, “In Taiwan, a spate of deaths at gaming cafés is raising a question: why is it that some of us are playing games beyond the limits of our physical well-being?” Author Simon Parkin vows to take us deep into obsession, the fuel that drives people to remain in virtual worlds so long they shuffle off their mortal coil, so to speak.

That question isn’t meaningfully answered or rigorously examined in Death by Video Game. In fact, the book hardly covers it. The challenge of this book should have been to get real, compelling insights out people who game past their mortal limits. Instead the book lacks rich, in-depth interviews and source material from those who are perhaps closest to “death by video game,” compulsive and competitive gamers who play for days at a time. What are their lives like? Why do they play? What are their happiest, and darkest, moments and memories? These basic questions go mostly unanswered in Death by Video Game.

There are a few interviews with self-confessed ex-World of Warcraft addicts—none with current addicts. One subject embodied the gamer stereotype: he was a filthy unemployed layabout who lived in a slum apartment, but in the game he was a god! The other subject mentions that being mathematically gifted and spreadsheet-minded gave him a leg-up on finding answers in the game, and pursuing said game knowledge and understanding game concepts on a deeper level drew him in. Parkin doesn’t delve into this concept—that a great deal of the time a high-level gamer spends fixated on their addiction is actually time spent learning, experimenting with, and exploring the game’s math or inner machinations in much the same way a coder spends as much time on Stack Overflow as he spends actually writing lines of code.

“In other words, with games, learning is the drug.” – Raph Koster, A Theory of Fun for Game Design

Parkin misses the point: “For each of these players around the world, video games provided a clear and, crucially, an achievable goal—one that came with the promise of peer approval and kudos.” How about, as long as you’re learning something and doing something successful with that knowledge, the drive to learn and do more is insatiable?

Though the topic of competitive gaming is covered, Parkin didn’t manage to speak with a professional competitive gamer. In the end of the book he returns to Taiwan, where the titular gaming deaths occurred. The cafe gamers comment that they “only” play for 24 hours a day, and then they disparage their peer who died playing a bit longer than they do. I would have flunked my journalism school assignment if I traveled to a foreign country, paid a translator, and then came back with those wimpy quotes.

I suppose the quotes weren’t important because the concept of the book was debunked in the first chapter. “Any activity that compels a human being to sit for hours on end without moving is, arguably, a mortal threat,” the author concludes. Within the first ten pages, the book’s premise is dead—as dead as those Taiwanese gamers. In 2016 The Independent gave us this gem of an article, “Binge-Watching TV Can Actually Kill You, Study Finds.” During the Japanese study in question, which followed the TV-watching habits of more than 86,000 people, 59 deaths from pulmonary embolisms were recorded. The number of hours spent watching TV was the primary marker of pulmonary embolism. Sounds like dying while gaming, or due to sedentary time spent gaming, ought to be more common, not so unusual it’s worthy of a book premise. Parkin acknowledged this fact, but failed to adjust the book’s hypothesis accordingly.

Though the death flair on Simon Parkin’s premise makes it tantamount to nonsense, there’s still a question there worth asking. Why do some people prefer the world of games to reality? Why do some play for days at a time, neglecting themselves, their habitat, responsibilities, finances, or relationships? When it comes to these authentic questions, Parkin editorializes about challenge, rewards, and control. He relies more often than not on his own assumptions—simplistic ones that we at Co-op Gaming Dot Info use casually on this site. Escape from the everyday. Comfort and challenge. Glory and accomplishment:

“Video games, at times, bring comfort. Often they bring challenge, relief, glory, discovery, even a glimpse of a fairer existence. They reward you for your efforts with empirical, unflinching fairness. Work hard in a game and you advance. Take the path that’s opened to you and persevere with it and you can save the world. Every player is given an equal chance to succeed. There is a prelapsarian quality to video games that makes them irresistible, especially to people whose experiences in life have been of injustice and unfairness.

“Games offer conflict within safe bounds, so perhaps it has to do with the human desire to be heroic, to perform acts for which they might be remembered, to stave off death’s great whitewash. Or perhaps it is the competitiveness of the athlete: the desire to win and assert dominance over our peers and rivals? Or is it to do with friendship and community, showboating and braggadocio?”

Do any of us as gamers turn on our machines every night to experience “fairness?” No. In fact, howling about our unfair treatment at the hands of gankers, cheaters, or the game’s creators is the usual scenario. Do any of us power up expecting glory? Even if we feel good about our accomplishments in a game, the feeling falls far short of anything that could be considered successful, rewarding, or glorious, at least socially. I don’t know about your friends, family members, and coworkers, but mine were completely nonplussed to hear John and I had obtained high-ranking positions on the Elder Scrolls Online leaderboard. It was a shameful confession—far from bragging. Progress, achievement, and reward may comprise the backdrop of our gaming experience, but they’re not at its core. What drives us to play video games, I believe, is far more simple. Here’s where I’m going to start editorializing.

“And the repetitive movements required to create a pattern release calming serotonin, which can lift moods and dull pain, according to the findings.”

This quote comes from an Independent article titled, “Knitting Can Reduce Anxiety, Depression, Chronic Pain, and Slow Dementia, Research Reveals.” I’d bet my life that the same effects holds for video games. We like to overlook the fact that video games are, at their core, acts of simple repetitive motion. We yammer about game systems, menus, gameplay, loot, story lines, and animations. But when we game, we’re pressing buttons. We’re tapping. We’re clicking.

Is gaming like knitting? No. It’s like a speed knitting competition in which a computer, second by second, determines and alters the patterns each contestant must knit. Video gaming is far more urgent than knitting. One mistake costs us the entire scarf. We’re performing millions upon millions of repetitive motions, and we must perform them in the most precise, controlled, and well-timed manner. Execute the perfect combo—sequence your buttons in perfect harmony with the enemy’s movement. Drag your cursor to the enemy’s head in a fast, fluid motion and click once—the satisfaction of a perfect headshot. It’s the soothing repetitive-motion release of serotonin that we crave, not the feeble PlayStation trophies, loot explosions, kill/death reports, and completion notifications. And seeing a streamer, AKA master-knitter, knit a perfect scarf, using hundreds of motions in perfect synchronicity with the computer, in real time, impresses the hell out of us.

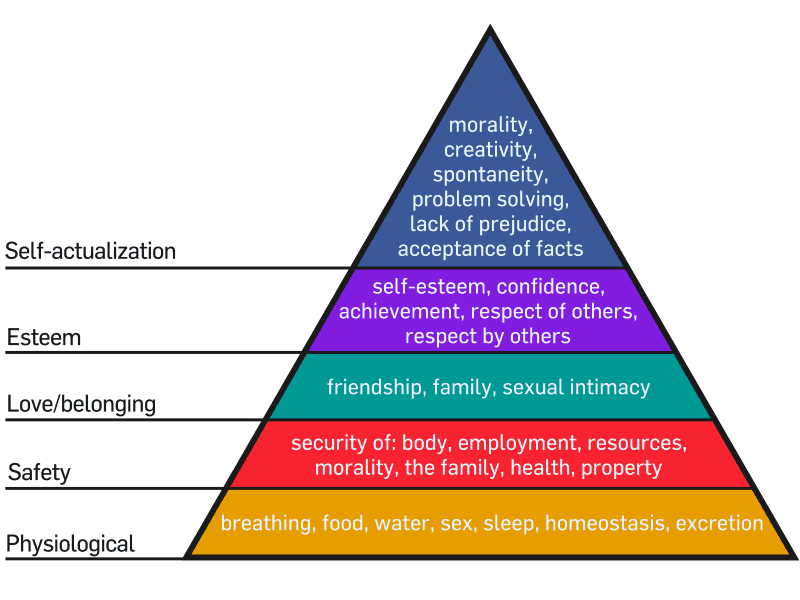

Back to the book—what if Parkin’s meandering thoughts are valid? Let’s say games satisfy our desires for challenge, relief, glory, conflict, friendship, and discovery. Let’s take a look at Maslow’s hierarchy of needs:

Wow, so video games vaguely fulfill the entire top portion of the pyramid—self actualization, esteem, and belonging/love. Maslow suggested we’d have to feed, clothe, and protect ourselves before we climb to the dazzling peak of the mountain. But if the peak presents itself for conquest every time we turn on our gaming system, certainly we prefer to dispense with the bottom half of the pyramid. Why take the time to sleep or shovel food into our mouths when the sweet ambrosia of self-actualization is available at the click of a button?

I’d like to hear more about this topic and how it relates to addictions of all kinds, but I didn’t find it in Parkin’s book. Death by Video Game conspicuously lacks even a single interview with a psychologist. With “Death by Video Game” as the working title, speaking to a psychologist familiar with video games ought to have been a priority. What author would write “Death by Opiates” without speaking to mental health professionals?

I admit that in 2015, when the book was published, there was no Fortnite. There were no concerned parents prying controllers out of their childrens’ hands and toting them to shrinks. But there was, and has always been, video game loot. Death by Video Game not only omits all discussion of gaming addiction and mental health, but also omits the entire topic of loot. These two glaring omissions made the book feel bewilderingly outdated. It felt so outdated that I casually told John it was published in 2006; I was shocked to discover it was actually published in 2015.

I have already dedicated nearly as many words in this review to the title and topic of the book as Parkin did in the book itself. Chapter 2 is when all topics relating to the title are dropped. So what does the meat of the book cover? A variety of interesting and notable gaming events, topics, and individuals. The reader goes on a gaming tour around the world and into the past; the pithy magazine-journalism style carries the reader from one anecdote or interview to another in a pleasant, engaging, and informative manner.

There’s plenty of neat info for someone like me who hasn’t been gaming since the 1980s. The discussion of MUDs and the interview with Richard Bartle were fascinating and prompted me to look up and read Bartle’s paper, “Hearts, Clubs, Diamonds, Spades: Players Who Suit MUDs.” I appreciated learning of the existence of The Guild Leader’s Handbook: Strategies and Guidance from a Battle-Scarred MMO Veteran and of sociologists and economists interest in EVE Online and its Council of Stellar Management. The reader of Death by Video Game meditates on diverse people and subjects, from gamers looking for Bigfoot in Grand Theft Auto V to a husband using Skyrim to cope with the loss of his unborn child. You find out that the combined rent and bills on the Team Dignitas house in 2015 was around $5,500 per month, and Riot paid it. The book is well-researched and well-written. It’s fun to read. But it ought to have been called “Charming—and Sometimes Sordid—Tales of Gamers and Gaming from Around the World.”

Death by Video Game: Review

Death by Video Games is interesting, but too shallow to satisfy.

3