At this very moment, somewhere in some derelict, tax-burdened, crime-ridden metropolitan hell-hole, an adorable little grey bird totters across a sidewalk. A man (or woman) swings his (or her) leg toward the innocent creature. Though the ill-timed kick badly misses the bird, it opens its wings and does a little flutter-hop to get away. “Filthy, vile little bugger!” shrieks the person. “Pigeons spread disease!”

Who hasn’t heard that line before? I’ve always wondered where the idea came from. After all, everyone’s heard that rats spread the plague (although that idea, too, is likely false). What major epidemic did pigeons spread? Everyone’s heard, too, that rat feces transmits hantavirus and a long list of other diseases. Nobody I asked could name a single illness pigeons spread.

These days, if you research online, consensus says that urban pigeon droppings almost never transmit disease to human beings. The risk is greatest during large-scale cleanups during which people scrape and churn the feces of hundreds of birds all at once; but even then, people almost never get sick. And also, the diseases pigeon poop can possibly spread are few: one bacterial (Psittacosis) and two fungal (Cryptococcosis, Histoplasmosis) infections. The majority of online fear-mongering and anti-pigeon sentiment comes from extermination and bird-spike companies; not public health agencies. Pigeon-related illness is definitely not something hospitals deal with on a daily, or even yearly, let alone centennial, basis.

Pigeons, unlike rats, are a domesticated species. Thousands of years ago, people started keeping flocks of rock doves. Used as messengers, pets, food, and for sport, pigeons have gone hand-in-beak with human beings for pretty much all known history. There was a time during which every big, prosperous European estate had its own dovecote—a special structure whose sole purpose was to house a pigeon flock. In fact, human beings are mainly responsible for pigeons’ proliferation across the world’s cities. They were brought there as welcome guests! So why do so many people today in the United States call them “rats with wings”?

I believe I found the answer in Mushrooms, Molds, and Miracles, a 1965 book. The following passage tells the story of the discovery of Cryptococcus neoformans in pigeon droppings and the subsequent pigeon murder campaign that swept the Western world.

About 1,000 deaths a year are attributed to the two severe forms of histo [Histoplasmosis]. This figure is only an approximation, however, since the disease is not reportable in many states. The other common respiratory infection of fungal origin, coccidioidomyosis, can also cause death. One in 1,000 of those infected by the fungus develops the serious form of this disease, which has a mortality rate of 50 percent. Coccidio also masquerades as tuberculosis and a wide number of other illnesses.

During the last few years [the early 1960s], health officials noting the connection of bird droppings and mycotic diseases have been turning a look of utter loathing on pigeons and starlings. But worse was yet to come. In September of 1962, the Bureau of Laboratories of the New York Department of Health, while investigating two recent deaths, discovered a deadly fungus in pigeon droppings. The organism, Cryptococcus neoformans, can, like its fellows, produce minor infections or fatal illness. In its severe form, it attacks the brain and the central nervous system.

“The central nervous system furnishes a peculiarly well-suited medium for the particular nutritional desires of this fungus,” reported doctors at a recent symposium on fungus infections.

About 20 cases of this form of cryptococcosis occur in New York City alone each year, and four of them end in death, the bureau reported. This announcement was a declaration of war on pigeons. Battle lines were quickly drawn. One suburban community sprayed the environs with repellent “Roost-No-More” and put up signs with the dogmatic message: “DO NOT FEED PIGEONS. PIGEONS ARE THE GREATEST DISEASE CARRIERS.” In Buffalo and in Indianapolis, the exterminators shot down the birds. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, on the other hand, belligerently declared its readiness to fight efforts to kill pigeons. And bird lovers reminded one another that there had once been an attempt to kill eagles in the belief that they carried off infants.

Cryptococcosis is also found in Europe, and there, too, the pigeon war is on. In West Berlin poisoned bread crumbs are spread on the streets. When this was first done in 1962, the exterminators did not get up early enough in the morning to foil the pigeon supporters. Waiting and watching unseen, they sneaked out as soon as the crumbs were laid and swept them up. It took authorities a year to muster up the energy to try again. This time, bird fanciers yielded to the inevitable. By the end of the year, 40,000 pigeons lay dead.

Mushrooms, Molds, and Miracles by Lucy Kavaler, 1965

In this passage there’s plenty to ponder. One thing is clear: There was an enormous anti-pigeon campaign in this country in the early 1960s. People were actually told (in so many words) that pigeons caused four deaths per year in New York City. If that were true, pigeons would be fairly notable little murderers. No wonder people’s parents or grandparents were careful to pass on the message that “Pigeons are the greatest disease carriers!” However, the Bureau of Laboratories of the New York Department of Health never proved that pigeon droppings made anybody sick. They merely connected the dots because they discovered a dot to connect.

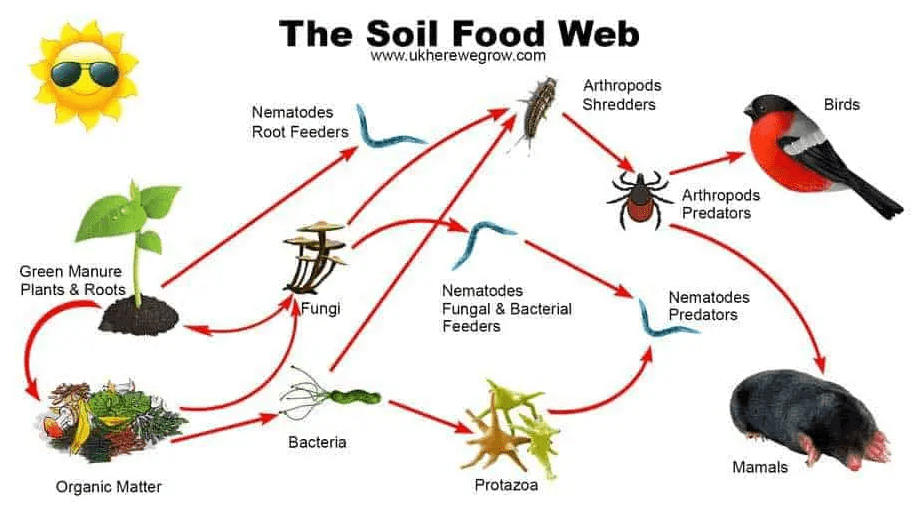

Today, Cryptococcus neoformans, the fungus mentioned in Lucy’s book, isn’t even listed as a disease pigeons can pass on to people. If you read about Cryptococcus neoformans on the Web, the first thing you see is that it lives in the environment throughout the world. It lives in the soil! It lives on rotten wood! So why are potentially harmful bacteria and fungi present in bird droppings, anyway? The soil food web, of course!

Birds eat insects, worms, seeds, and other tasty morsels out of the dirt. Birds (and their feces) thereby become inculcated by fungal spores, soil bacteria, heavy metals, toxic pesticide residues, and anything else in the soil. If New York City pigeons were found to have Cryptococcus neoformans in their poop, that only means they pecked it off the streets of New York City itself. Those four deaths in 1961 could have just as easily been caused by breathing alley dust. Demonizing birds on the basis of the soil-based life forms they may or may not harbor or excrete in their droppings is basically the same as demonizing soil itself. By that logic, any and all dirt should be scrubbed off city streets. Know what else lives in soil? Anthrax! There’s definitely a lot of ignorant folks in this world who do demonize soil, too. I wish they would wake up one day and realize that they themselves are nothing more than a large tube stuffed with bacteria, viruses, and fungi.

The second thing you’d see on the modern Internet if you read about Cryptococcus neoformans, the fungus mentioned in Lucy’s book, is that clinical reports are uncommon and the disease is poorly documented. This brings me to the part of the passage in Mushrooms, Molds, and Miracles that said, “Coccidio [another fungal infection] also masquerades as tuberculosis and a wide number of other illnesses.”

All respiratory illnesses resemble one another. The respiratory system musters up a similar set of responses (coughing, sneezing, mucus, stuffy nose, etc.) whether it’s fighting off a fungus, bacteria, or environmental toxin. Back in the 60s, when tuberculosis was a deadly scourge and very little diagnostic lab work was performed to determine whether any given patient had TB or any one of the other quintillion known respiratory ailments, people lived in fear of coming down with a never-ending, potentially deadly respiratory ailment. It’s no wonder they went ape-shit when they were told that pigeon poop could cause any type of respiratory illness, let alone a deadly one.

Still, people should have known better than to murder pigeons. People should have stopped and thought about their own poop, which can transmit cholera, typhoid, hepatitis, polio, cryptosporidiosis, ascariasis, and schistosomiasis. I won’t attempt to estimate how many orders of magnitude more likely it is that any given person ingests another human being’s shit, either by eating ass or by changing a baby or elderly person’s diaper, several times over the course of his or her lifetime, than breathes bird feces.

People should have remembered that pigeons are a domesticated animal, and that people kept pigeons for thousands of years. People should have remembered that people have lived in urban environments with pigeons for thousands of years, and that nobody ever dropped dead from stepping on a pigeon turd. It certainly makes me sad to think of the 40,000 dead pigeons of 1963. However, I’m comforted by the fact that today, some people estimate the population of pigeons to be greater than that of human beings. Long may they have the majority!