If you’re a pigeon fancier like us at Co-op Gaming Dot Info, you’ve probably imagined how loveable a giant dove, let’s say 50 pounds, could be. He and his flock would roam the earth like buffalos, belting out enormous coos and dancing in the horizon, their silhouettes like pom-poms beating in harmony with the breeze. They would be ideal houseguests: smarter than dogs, more cuddly than rabbits, and perhaps a touch less irascible than parrots. Imagine our horror when we discovered that our fantasy was the reality of the past.

Dodos were, in fact, doves. They and the famed Passenger Pigeon weren’t the only magical, mysterious, beautiful doves driven to extinction by 18th and 19th century explorers and peoples, who punted them like so many soccer balls into the sunset, never to be seen again. What follows is the “Gentle Doves” chapter of the book Vanished Species by David Day, 1981. You won’t find this long, depressing account of our friends the doves’ demise anywhere else online; we transcribed it without permission, scanned the images, and allowed Google to populate it with crappy online advertisements, just for our readers at Co-op Gaming Dot Info.

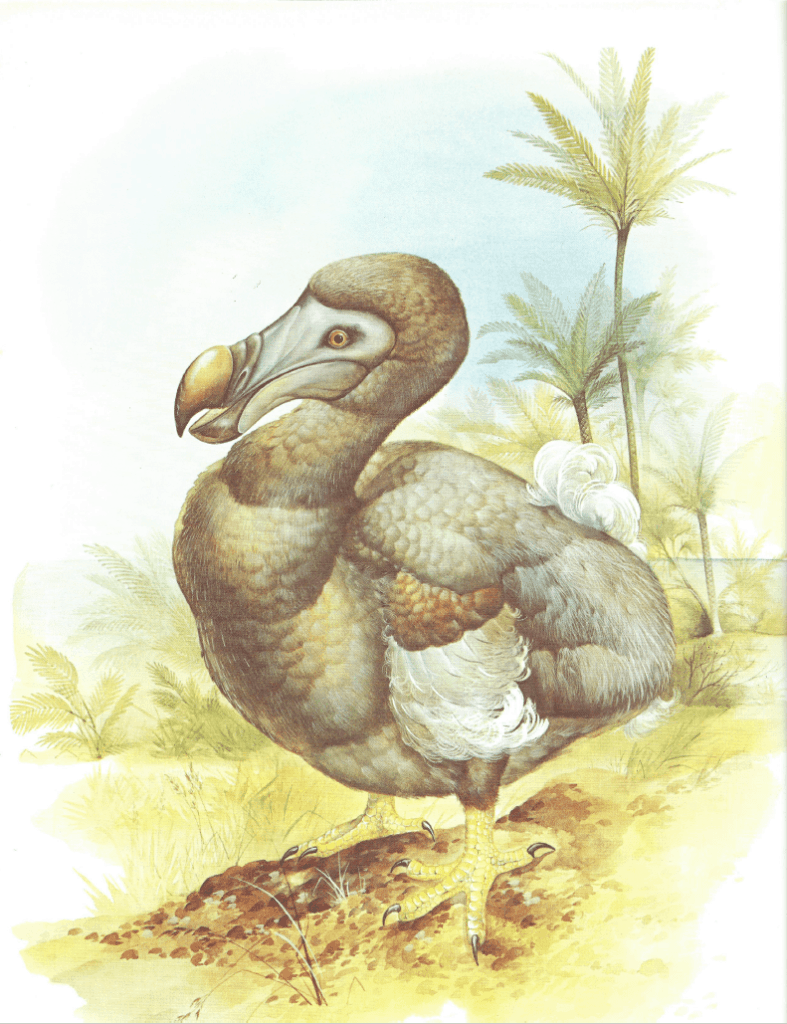

Every schoolchild knows the Dodo, the butt of so many jokes about stupidity and obsolescence. The fate of the peculiar bird that once lived on the island of Mauritius some 800km (500 miles) west of Madagascar, is well known to all. The Dodo is as sadly famous for its extinction, as the mythical Phoenix is for its resurrection.

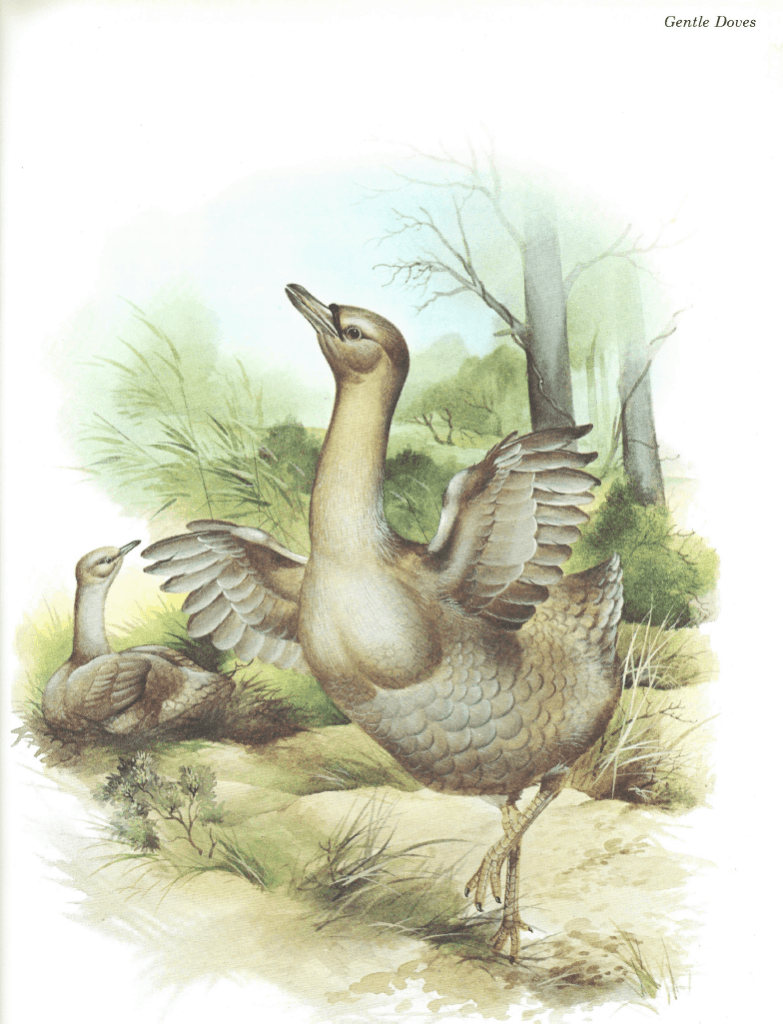

The first explorers of Mauritius variously labelled the Dodo: a wild turkey, a cassowary, a ‘hooded swan,’ a booby, and a ‘bastard ostrich.’ In fact, the Dodo was a large flightless dove which, primarily because of its gentle dove-like qualities, became extinct in 1680.

The Dodo (Raphus cucullatus) was without doubt the largest and strangest dove ever to have lived. Its appearance fascinated the first European observers. Among the earliest accounts of the Dodo is one left by the Englishman Sir Thomas Herbert, who visited Mauritius in 1627: ‘First, here and here only . . . is generated the Dodo, which for shape and rareness may antagonize the Phoenix of Arabia: her body is round and fat, few weigh lesse than fifty pound, are reputed of more for wonder than for food, greasie stomackes may seeke after them, but to the delicate, they are offensiue and of no nourishment.

‘Her visage darts forth melancholy, as sensible of Nature’s injurie in framing so great a body to be guided with complementall wings, so small and impotent, that they serue only to prove her bird.

‘The halfe of her head is naked seeming couered with a fine vaile, her bille is crooked downwards, in midst is the thrill, from which part to the end tis of a light greene, mixt with pale yellow tincture; her eyes are small and like to Diamonds, round and rowling; her clothing downy feathers, her traine three small plumes, short and inproportionable, her legs suting to her body, her pounces sharpe, her appetite strong and greedy.’

Although Mauritius had undoubtedly been visited by Arab traders before the Portuguese ‘discovered’ the Mascarene islands in the early 16th century, no human settlements had been established. So, until the Portuguese came, Mauritius remained much as it had been for tens of millions of years. Like so many remote island groups the Mascarenes had no mammals, but were dominated by birds. As an early observer noted: ‘The birds (of which the island is full) are of all kinds: Doves, Parrots, Indian Crows, Sparrows, Hawks, Thrushes, Owls, Swallows, and many small birds; white and black Herons, Geese, Ducks, Dodos . . . ’ The birds adapted to take maximum advantage of their habitat and evolved into many unique, strange, and colorful species. When the European ships arrived this unique collection of birds provided the crews with easy food and sport, for the birds, with no experience of predators, would often walk right up to their destroyers. One can imagine the novelty these birds presented to the sailors, who, confined to meagre rations for many weeks and months, must have relished the thought of so much fresh, available meat and easy sport.

The Portuguese were followed by the Dutch in 1598, when Cornelius Van Neck made Mauritius a Dutch possession. After that time, many ships stopped there on their long journeys across the Indian Ocean and indulged in countless pathetic slaughters of the unwary birds. Another Dutch captain reported: ‘We lived on Tortoises, Dodos, (Pink and Blue) Pigeons . . . Grey Parrots and other game, which the crews caught by hand.’ None of these animals are now found on the island, except the Mauritian Pink Pigeon, of which there are less than twenty individuals in the world today.

Despite the slaughter of wildlife carried out by the hundreds of European ships that visited Mauritius, the Dodo survived. In the more inaccessible parts of the island, breeding colonies remained elusive enough to escape marauding seamen. But in 1644, the Dodo’s fate was sealed, for the island became a Dutch colony. The colonists seemed to display a grim dedication to the cause of exterminating the Dodo, although the bird was neither a nuisance nor a menace, and, according to most accounts, its flesh was very poor eating, being tough and rather bitter. There must have been little sport in walking up to an almost tame bird and crushing its skull with a wooden club. As the birds could not fly, and any able-bodied man could run faster, the outcome of any hunt was a foregone conclusion.

Beyond the outright slaughter of Dodos carried out by men, other equally devastating enemies accompanied the colonists. For the settlers brought with them not only their pet dogs and cats, but also monkeys, swine, and the inevitable rat. These creatures readily adapted to the island’s wilderness and rapidly cleared it of Dodos, even in the areas most inaccessible to men. Roaming dogs were most effective at destroying the adult birds, while cats, rats, monkeys, and pigs quickly rooted out both eggs and chicks. Ironically, in this tropical land the wold domestic animals multiplied at such a rate, they became the nuisance that the birds had never been. At one point a plague of rats was so severe that it caused the ‘Hollanders’ on the island to emigrate. The destruction caused by feral pigs to the forests and farms became so great that a hunt was organized in which 1500 were killed in a day. That same year a chronicler also mentioned a single garden in which 4,000 monkeys frolicked. By 1680, the island was completely overrun by men and the animals they had introduced, and that unique creature called the Dodo was gone forever.

The Dodo of Mauritius was not the only species of giant dove in the family Raphidae; there were three others. Two of these were the Dodo’s elegant cousins, the Solitaires; one of which lived on the island of Reunion 160km (100 miles) to the southwest of Mauritius, while the other inhabited Rodriguez some 480km (300 miles) to the east.

According to the journals of all who saw the Solitaires, they were accounted both delightfully beautiful and delightfully edible. Indeed, the earliest observer of the Solitaire of Rodriguez (Pezohaps solitarius) seemed almost enraptured in his description of the birds.

‘The Females are wonderfully beautiful, some fair, some brown; I call them fair, because they are the colour of fair Hair. They have a sort of Peak, like a Widow’s upon their Beak, which is of a dun colour. No one feather is straggling from the other . . . The Feathers on their Thighs are round like shells at one end, and being there very thick, have an agreeable effect. They have two Risings on the Craws, and the Feathers are whiter there than the rest, which lively represents the fine bosom of a Beautiful Woman. They walk with so much stateliness and good Grace, that one cannot help admiring and loving them.’

The writer, Francois Leguat, was a remarkable man—a Huguenot refugee from France who had spent two years of his exile on the previously uninhabited Rodriguez. His descriptions of the Solitaires, published in his 1708 memoirs, were considered fanciful for two centuries until archaeology proved that so much of what he said was true and the rest must be taken seriously. He describes their mating dances and displays, when they whirred their short wings and clapped them ‘like a rattle’ against their sides. He tells how they guarded their single chicks, driving off all other Solitaires from their territory, and how they mated for life—’these two Companions never disunite.’ But his most remarkable description is of their annual ‘bethrothal’ ceremonies: ‘Some days after the young one leaves the nest a Company of 30 to 40 brings another young one to it; and the new-fledged Bird with its Father and Mother joyning with the Band, march to some bye Place. We frequently followed them, and found that afterwards the old ones went each their way alone, or in Couples, and left the two young ones together, which we call a Marriage.’

Leguat was not the only traveller moved to talk of this graceful long-necked bird in human terms: 30 years later another wrote: ‘When caught they make no sound, but shed tears,’ and said that they pined away quickly, refusing to eat in captivity.

Unlike their portly cousin from Mauririus, the Solitaires could be aggressive: they pecked fiercly and their apparently useless wings had knobs ‘the size of musket balls’ at their tips with which they could strike as well as making that rattling sound. All in all they seem to have earned more respect from their human visitors than their relatives on the other islands.

Yet, the Solitaire—despite its ‘usefulness,’ ‘intelligence,’ and ‘beauty’—soon became quite as extinct as its ‘useless,’ ‘stupid,’ and ‘ugly’ cousin, the Dodo of Mauririus. Though it was still reportedly alive in 1761, a long-time inhabitant of Rodriguez in 1831 had never seen or heard of the Solitaire. It was certainly gone by 1800.

The Reunion Solitaire (Ornithaptera solitarius) seems to have been a slightly larger and more sturdily built bird than the Rodriguez species. Its legs were longer and muscled as if for running at greater speeds. It also had a large tuft-like feathered tail, while its cousin had practically no tail at all. Like the Rodriguez species it was extensively hunted for food, and, probably because it was a much better tasting bird, it became extinct around 1700, a good 70 years before its relative on Reunion, the White Dodo.

Both Solitaires might have been forgotten altogether, dismissed as fairy-tale birds, had not several skeletons on Rodriguez been unearthed in 1875 and later, and proved that Leguat’s descriptions of the birds, including the widow’s peak and the ‘musket-ball’ wing-clappers, had been in every way accurate.

No such evidence exists to testify to the existence of the fourth Didine species: the White Dodo of Reunion (Victoriornis imperialis.) Yet two vivid eye-witness accounts and a number of paintings, one of high-quality, have persuaded scientists that the bird did exist and differed in significant ways from the Mauritian Dodo.

In an account of a voyage by Captain Carleton in 1613, J. Tatton wrote of Reunion: ‘There is a store of Land-fowl, both small and great, plentie of Doves, great Parrots and such like; and a great fowl of the bigness of a turkey, very fat, and so short-winged that they cannot flie, being white, and in a manner tame; and so are all other fowles, as having not yet been troubled or feared with shot.’ Needless to say this state of affairs was short-lived. This Dodo was obviously as defenseless as its Mauritian counterpart—witness this 1646 description by a Dutch traveller: ‘There were also some Dod-eersen which had small wings, but could not fly; they were so fat that they could scarcely walk, for when they trod their belly dragged along the ground.’ It should be pointed out that the Dodos’ waistlines varied with the season (some authorities even believe that they shed their horny bill-sheaths once a year as part of the general moult and wasting) but the picture, once again, is one of defenselessness.

How long the White Dodo survived can only be guesswork: possibly as late as 1700. Only the greater size of Reunion, and the slower growth of settlement seems to have allowed it to outlive the Mauritian Dodo so long. It is not impossible that the very last White Dodo died in Europe, for the Governor of Mauritius and Reunion between 1735-46, de la Bourdannaye, sent one to the Directors of the Company ‘as a curiosity.’ It must have been one of the last, if it survived the journey.

The accurate, or at any rate convincing aquarelle paintings by Pieter Withoos in 1680 show that at least one White Dodo did reach Europe alive and he pictures it in a park among common European waterfowl which are accurately represented.

He portrays the Dodo with buttercup-yellow wings, a high-arched tail, and a faint bluish tint toward the end of its otherwise white plumage. The eyelid was bright red, the legs and feet were ochre-yellow, with black nails (proving that it was not an albino), and the beak far less hoooked and pointed than the Mauritian Dodo’s. Ungainly it may have been, but in its tropical native setting it must have looked spectacular.

If the curiosity collectors who brought both Dodos for exhibit in Europe had any of the sense of mission shown by the better modern zoos, these giant doves might today be at large in our parks, however doomed their native habitat. A creature that could survive the sea voyages of that period was tough—it could have survived and it probably would have bred.

One of the Dodo family was on show in the London of Charles I when, in 1638, Sir Hamon Lestrange saw its poster picture on display and went to look. He saw ‘a great fowl, somewhat bigger than the largest Turkey Cock . . . but stouter and thicker and of a more erect state . . . The keeper called it a Dodo, and in the end of a chymney in the chambers there lay a heape of large pebble stones, whereof hee gave it many in our sight, some as big as nutmegs and the keeper told us she eats them (conducing digestion) . . . ’

Members of the Dodo family certainly did eat stones—they held them in their gizzards to crush food; ‘bezoars’ are invariably found with the skeletons of Mauritian Dodos and Solitaires and were, for a time, valued for their ‘medicinal’ properties. Nevertheless, the thought of the bird being fed stones in a dark London house, 6,000 miles from the sunny Mascarenes, is a depressing one.

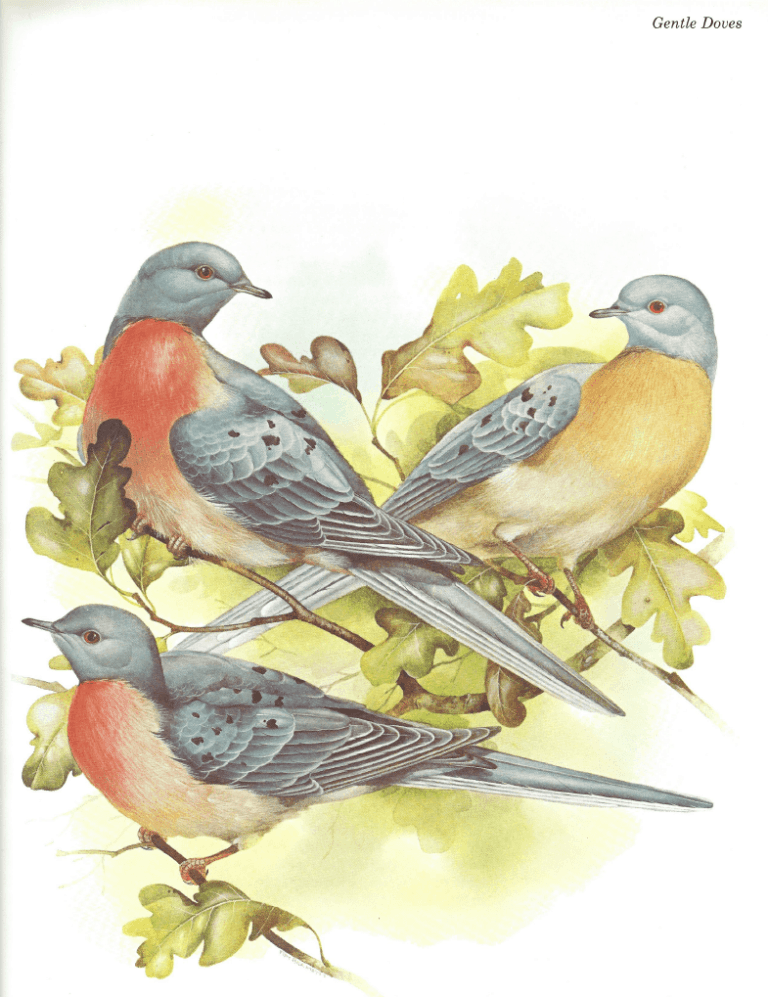

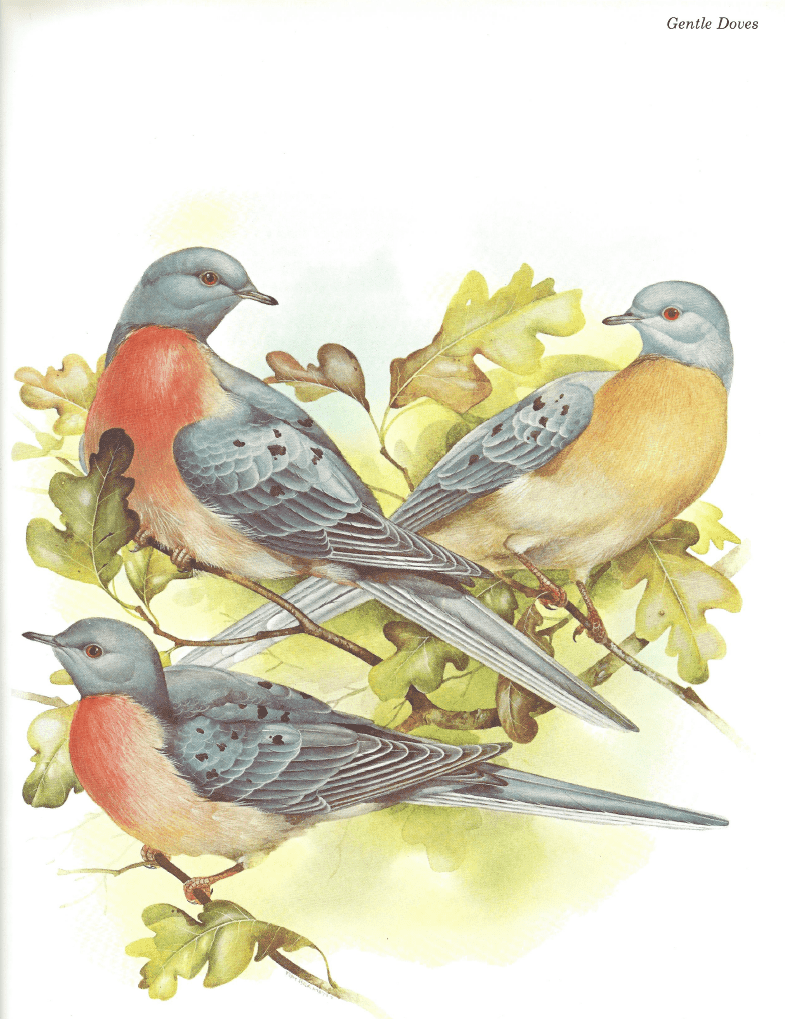

After the Dodo, the Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) is certainly the most famous case of animal extermination. It is also the most astonishing and unbelievable of all extinctions.

As the Elephant Bird of Madagascar was without a doubt the largest bird ever to live, the Passenger Pigeon or Migrating Dove was the most numerous. As late as 1860 any naturalist or layman might easily have argued that the Passenger Pigeon was, in biological terms, the most successful species of bird on earth. Its numbers were so great, its territories so vast, and its strong body so well-designed for its needs and habitat, that it is almost incredible that it could have been exterminated within the short space of 50 years.

No one knows how many Passenger Pigeons there were, but it has been estimated that they accounted for nearly 40 percent of the entire bird population of North America. In 1870, when their numbers were considerably diminished by relentless hunting, a single flock 1.6km (one mile) wide and 510km (320 miles) long, containing not less than 2,000 million birds, passed over Cincinnati on the Ohio River.

The noted American ornithologist Alexander Wilson went in 1806 to a Passenger Pigeon breeding ground in Kentucky. It was 64km (40 miles) in length and several miles wide. The ground was scattered with the broken limbs of trees, dung, masses of eggs, and squab chicks which were being fed upon by herds of hogs. The trees each held more than a hundred nests. He wrote of a great flight of these birds going to a nesting site of equal size some 96km (60 miles) away. The Pigeons were traveling at the speed of a mile a minute and high beyond the reach of gunshot, very close together and many layers deep: ‘. . . as far as the eye could reach, the breadth of this vast procession extended; seeming everywhere equally crowded.’ He calculated the number of birds to be 2,230,272,000. On the modest assumption that each bird consumed half a pint of nuts and seeds a day, he estimated this clock would consume 17,424,000 bushels each day.

Similarly, in the autumn of 1813, that most famous of ornithologist and illustrators, James Audubon, was traveling in a wagon from his home on the Ohio River to Louisville, Kentucky, some 88km (55 miles) away, when a column of Passenger Pigeons filled the sky so the ‘light of noonday sun was obscured as by an eclipse.’ At sunset he reached Louisville and still the birds passed over in a solid mass. For three days other flocks followed this first one. Audubon calculated the size of only one of the columns of birds. He estimated that a flock of birds one mile wide passing overhead for three hours at a mile a minute would equal 1,015,036,000 creatures. He also estimated that this clock would consume 8,712,000 bushels of feed a day.

Like Wilson, Audubon went to roosting and nesting sites. He saw huge broken limbs of trees and many trees, themselves more than 60cm (2ft) in diameter, broken off a few feet from the ground simply from the weight of the birds. The dung was so deep on the forest floor he mistook it for snow at first. When the flock returned there was unbelievable confusion and uproar; the wings of so many birds was like a gale and the sound of their landing was like thunder.

The Passenger Pigeon’s habitat seems to have been virtually the whole of forested North America, although its primary territory could be said to have been east of the Mississippi from the Hudson BAy to the Gulf of Mexico. The pigeons seemed to have fed primarily on the acorns and nuts of the hardwood forests, as well as the seeds of coniferous woodlands. They also fed on grains, grass seeds, all manner of berries, and some insects.

The great migrations of these birds seemed to have been related to food gathering conditions as well as breeding habits. When food was plentiful in the woodlands, they came together. When it was scarce they dispersed into small flocks. Passenger Pigeons were strong and swift fliers. They maintained constant speeds of more than 96km (60 miles) per hour, and were capable of flying 1,600km (1000 miles) in a day. Thus, despite their numbers, they seemed always capable of finding sufficient food because of their ability to range so widely in a matter of days.

In 1917, the Massachusetts State Ornithologist, Edward Forbush, recorded what he believed to the the best authentic description of the nesting habits of the Passenger Pigeon. It is an extraordinarily erudite account by a Chief Pokagon, a full-blooded American Indian said to be the last Pottawattomi chief of the Pokagon band.

‘About the middle of May, 1850, while in the fur trade, I was camping on the head waters of the Manistee River in Michigan. One morning on leaving my wigwam I was startled by hearing a gurgling, rumbling sound, as though an army of horses laden with sleigh bells was advancing through the deep forests toward me. As I listened more intently, I concluded that instead of the tramping of horses it was distant thunder; and yet the morning was clear, calm, and beautiful. Nearer and nearer came the strange commingling of sleigh bells, mixed with the rumbling of an approaching storm. While I gazed in wonder and astonishment, I beheld moving toward me in an unbroken front millions of pigeons, the first I had seen that season. They passed like a cloud through the branches of the high trees, through the underbrush and over the ground, apparently overturning every leaf. Statue-like I stood, half-concealed by cedar boughs. They fluttered all about me, lighting on my head and shoulders; gently I caught two in my hands and carefully concealed them under my blanket.

‘I now began to realize that they were mating, preparatory to nesting. It was an event which I had long hoped to witness; so I sat down and carefully watched their movements, amid the greatest tumult. I tried to understand their strange language, and why they all chatted in concert. In the course of the day the great on-moving mass passed by me, but the trees were still filled with them sitting in pairs in convenient crotches of the limbs, now and then gently fluttering their half-spread wings and uttering to their mates those strange bell-like wooing notes which I had mistaken for the ringing of bells in the distance.

‘On the third day after, this chattering ceased and all were busy carrying sticks with which they were building in the same crotches of the limbs they had occupied in pairs the day before. On the morning of the fourth day their nests were finished and eggs laid. The hen birds occupied the nests in the morning, while the male birds went out into the surrounding country to feed, returning about 10 o’clock, taking the nests, while the hens went out to feed, returning about 3 o’clock. Again changing nests, the male birds went out the second time to feed, returning at sundown. The same routine was pursed each day until the young ones were hatched and nearly half-grown, at which time all the parent birds left the brooding grounds about daylight. On the morning of the eleventh day after the eggs were laid, I found the nesting grounds strewn with egg shells, convincing me that the young were hatched. In 13 days more the parent birds left their young to shift for themselves, flying to the east about 60 miles, where they again nested. The female lays but one egg during the same nesting.

‘Both sexes secrete in their crops milk or curd with which they feed their young until they are ready to fly, when they stuff them with mast and such other raw materials sas they themselves eat until their crops exceed their bodies in size, giving them the appearance of two birds with one head. Within two days after the stuffing they become a mass of fat—‘a squab.’ At this period the parent bird drives them from the nests to take care of themselves, while they fly off within a day or two, sometimes hundreds of miles, and again nest.

‘It has been well-established that these birds look after and take care of all orphan squabs whose parents have been killed or are missing. These birds are long-lived, having been known to live 25 years caged.’

It really does seem inconceivable that a bird as numerous as the Passenger Pigeon could have been so rapidly exterminated. Yet the determination of the men who destroyed them was as extraordinary as the numbers of their quarry. In the 1850s a single New York merchant reported he was selling 18,000 pigeons a day. There were many others like him in New York, as well as Chicago, St Louis, New Orleans, Boston, and virtually every other city and town in northern and eastern America.

The demand for these birds was phenomenal. Adult birds were the cheapest meat that could be bought; the squabs were a tender delicacy. The gizzards, entrails, blood, and even dung were marketed as medical cures for gallstones, stomach aches, dysentery, colic, infected eyes, fever, and epilepsy. Pigeon down and feathers were used for pillows and quilts. There was also a large market for live birds. Sportsmen who indulged in trapshooting bought up perhaps a million birds a year. A shooting club for a week’s competition might bring 50,000 birds, nearly all of which would die either by being shot or having their wings or necks broken by being hurled from the catapult traps. One sporting gentlemen might kill 500 or more of these birds in a day’s shooting.

After 1860 pigeon hunting became a full-time occupation for several thousand men. With the advent of the telegraph and the railroad, hunters were able to follow and slaughter the migrating birds wherever they landed. From then on the nesting grounds were seldom safe. The birds were searched out, harried, and destroyed. Hundreds of railway boxcars were sent with the hunters and waited to be filled with the carcasses. Local part-time hunters generally used guns, clubs, poles, smudge pots, and even fire to kill the birds at nesting sites. The best professional hunters used huge, specially designed traps and nets. Some of the large nets were baited with decoy birds. These birds were called ‘stool pigeons.’ They were captured birds with their eyes sewn up and their legs pinned to a post or ‘stool.’ The fluttering wings of these blind birds attracted other pigeons which were then caught up in the huge nets and slaughtered. Some of the net traps were capable of capturing 2,000 birds at once.

The pressure of the hunters was relentless. As late as 1878, near Petoskey in Michigan, hunters descended on a nesting sight 64km (40 miles) long and 5 to 16 km (3 to 10 miles) wide. Their efficiency was astounding. In this one hunt it was estimated they destroyed 1,000 million birds.

By 1896 there were only 250,000 Passenger Pigeons left. They came together in one last great nesting flock in April of that year outside Bowling Green, Ohio, in the forest on Green River near Mammoth Cave. The telegraph lines notified the hunters and the railways brought them in from all parts. The result was devastating—200,000 carcasses were taken, another 40,000 were mutilated and wasted. One hundred thousand newborn chicks not yet at the squab state and thus not worth taking were destroyed or abandoned to predators in their nest. Perhaps 5,000 birds escaped.

The entire kill of this hunt was to be shipped in boxcars to market in the east, but there was a derailment on the line on the day of the shipping. The dead birds packed into the boxcars soon began to putrefy under a hot sun. The diligent hunters’ efforts were wasted: the rotting carcasses of all 200,000 birds were dumped into a deep ravine a few miles from the railway loading depot.

On 24 March 1900 in Pike County, Ohio, the last Passenger Pigeon seen in the wild was shot by a young boy. On 1 September 1914 in the Cincinnati Zoo, ‘Martha,’—a Passenger Pigeon born in captivity—died at 29 years of age. She was the last of her species. The impossible deed was done.

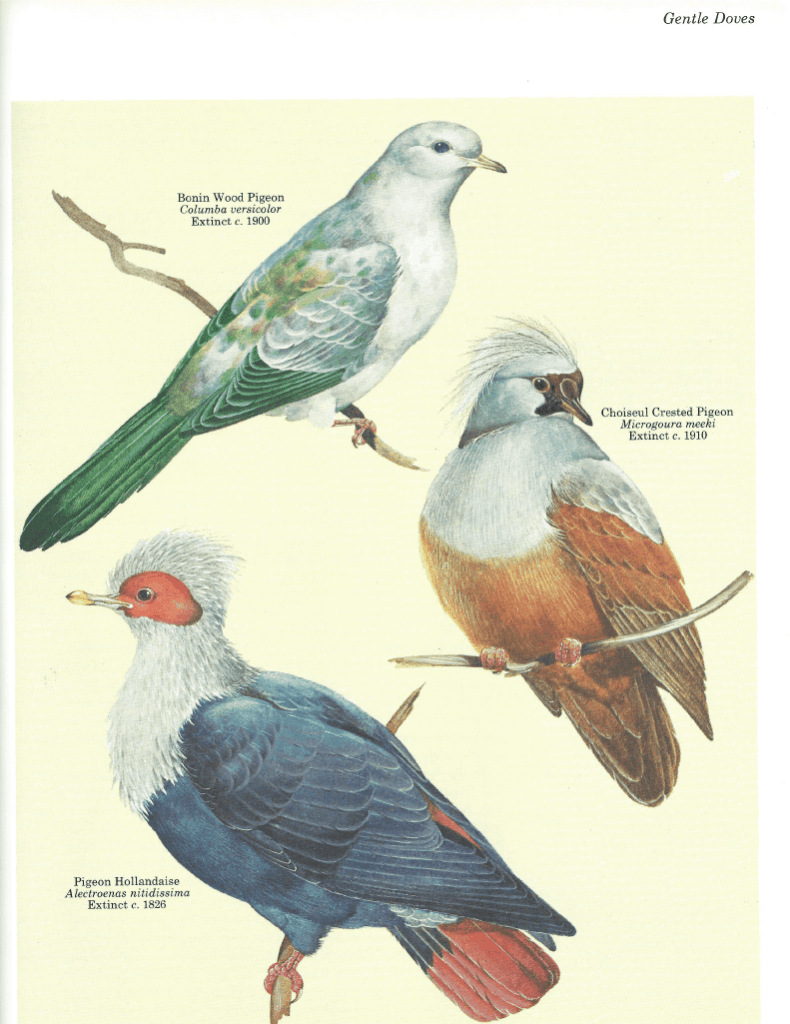

The Dodo was not the only pigeon to suffer extinction on Mauritius. There was also the striking crested Pigeon Hollandaise, which is commonly called the Mauritius Blue Pigeon (Alectroenas nitidisima.) Like the Common Dodo, it was endemic to Mauritius. This exotic Blue Pigeon did not suffer from the Dodo’s inability to fly, nor did it nest on the ground. It was a graceful forest bird that fed on fruit, berries, and seeds. It lived in large flocks and nested communally in trees. Again unlike the Dodo, this bird was delicious to eat. ‘Shooting parties’ were often organized by the resident Europeans for sport and food. There was also a peculiar catch-all bounty paid by the government from 1775 onward for the killing of all ‘vermin.’ ‘Vermin’ seems to have included pigeons, and practically every other wild creature on the island as well.

In the long run it was not the hunters, nor the imported dogs, cats, hogs, and rats that finally exterminated the Mauritius Blue Pigeon. It was the pet monkeys which the colonists had released into forests and allowed to breed in vast numbers. This same predator has reduced that other endemic dove, the strange Mauritius Pink Pigeon, to less than 20 birds today. The monkeys, capable of searching out the pigeons’ nests in the highest of trees, continually raided them for eggs. The result was that the Blue Pigeon could not sustain its numbers with the heavy mortality of both adults and young. The last specimen of the Mauritius Blue Pigeon was shot in 1826 in the Savanne Forest.

In the June of 1827 Captain Beechey in the HMS Blossom sailed into the Bonin Islands, which lie about 800km (500 miles) south of Tokyo harbour. He landed on the main island of the central group and named it Peel Island. Captain Beechey was the first to make mention of what we now know as the Bonin Wood Pigeon (Columba versi-color), a distinctly different species from the related Japanese wood pigeon. It was generally a much paler bird than its relatives, but had a strikingly colourful back, which was described as ‘metallic golden-purple.’

On the Blossom’s visit to Peel Island a considerable variety of birds was reported in great numbers, though shipwrecks had already resulted in numerous pigs and rats being released on the islands. Only 25 years later, in 1853 when Commodore Perry passed through the Bonin Islands en route to Japan, he stated that birds had become rare. At this time there were only 31 people on the Bonin Islands, but there were deer, goats, pigs, sheep, and ‘innumerable cats and dogs . . . where no mammals, except a bat had previously existed.’

In 1875 Japan annexed the islands. At that time there were only 100 people on the islands, but by 1900 more than 5,000 inhabited them. This rapid population growth seems to have ended the Wood Pigeons’ chances of survival. The forest fast disappeared. A man named A.P. Holst took the last specimen of the Bonin ISland Wood Pigeon from the island called Nakondo Shima in 1889. Between 1900 and 1929 various collectors searched the islands in vain for the bird.

Among the Solomon Islands of Melanesia is Choiseul, once home to the most spectacular of the Solomon Islands birds. The Choiseul Crested Pigeon (Microgoura meeki) is known only from six specimens, gathered by the Australian, A.S. Meek, in 1904. At that time the natives were thought to be hostile and it seems Meek acquired the birds in trade from a village and consequently did not know exactly what locality they came from. Modern ornithologists surmise that this pigeon inhabited remote cloud forests on the island’s interior.

The Choiseul Crested Pigeon was first named and described scientifically by Walter Rothschild, who bought some specimens in the year they were collected. Later expeditions in 1927 and 1929 by experienced collectors attached to the Whitney South Sea Expedition of the American Museum failed to find this beautiful pigeon.

Being one of the most exotic of the Solomon Islands birds, it was also one of the most specialized. It was largely ground-dwelling and it fed and nested very close to the forest floor. At the time of the American Museum expedition, the Melanesian natives said that the bird hadn’t been seen for many years, and they said themselves that introduced cats had killed them off.

South of the Solomon Islands, on the eastern rim of the Coral Sea, is the island of Tanna in the New Hebrides. Here lived another rare Melanesian pigeon, the Tanna Dove (Gallicolumba ferruginea).

Practically nothing is known about the history of this bird. All our information comes from the naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster and his son (the illustrator G. Forster) who were attached to the Second Pacific Expedition of Captain James Cook

In his Observations Made During a Voyage Around the World of 1778, Forester wrote that on 5 August 1774 Cook’s sloops, Resolution and Adventure, ‘anchored in a port on the new island which has a volcano. The natives call their island Tanna . . . its circuit appears to be about 24 leagues [100 km]. Forster spent a lot of time investigated the ‘Doogoos’, or hot springs near the tideline of the harbour, and watching the volcano 13km away erupting and creating a cloud ‘like a large cauliflower’. The expedition remained on the island for two weeks, during which time Forster discovered a dove unique to Tanna. On 17 August, Forster wrote: ‘We came into a wood . . . where a dove of a new species was shot. It is a small dove, with both head and breast a rusty brown, but what marks it off from the other new doves is the dark green wings and the strangely yellow eyes.’ Forster then follows this up with a much more comprehensive description noting in detail many other features, such as its black bill, red feed, grey belly and dark reddish-purple back. Later Forster made a study of the fruits and vegetables of the island. In the process he indirectly gives us a further detail concerning the bird’s diet. He does this by telling us how he first discovered the wild nutmeg of Tanna ‘without ever being able to find the tree’. It was found ‘in the craw of the pigeon which we shot . . . which disseminates the true nutmegs of the East Indian Isles.’

This is all we know of the Tanna Dove. It is only because of Forster’s report and his son’s illustrations that the world became aware of the bird’s existence – and of its passing.

Accounts of the Tanna Dove and the Choiseul Crested Pigeon lead one to suspect that quite a number of rare island birds may have disappeared without even being noticed or noted by the men who invaded their territories.

We know, for instance, that on Napoleon’s famous island of exile, St. Helena, there was a blue dove which was apparently extinct by 1775. Yet so little is known of the species, that no name has yet been assigned to it.

Of other extinct birds, such as the Norfolk Island Pigeon (Hemiphaga novaseelandiae spadicea) we know only marginally more. This subspecies of the New Zealand Pigeon inhabited the tiny Norfolk Island some 800km (500 miles) northwest of New Zealand. It is likely that cats, forest destruction and imported weasels, along with human hunting practices, were the causes of extinction. Further, it seems the Norfolk Island Pigeon could not adapt to imported plants as staples. The last recorded sighting was in 1801.

Another pigeon from an island in the Tasman Sea (between New Zealand and Australia) is now known to us only through a painting by Midshipman George Raper of HMS Sirius.

In 1790, the Sirius stopped at Lord Howe Island for water and supplies. It was here that Raper painted the Lord Howe Island Pigeon (Columba vitiensis godmanae). It was not until 1915 that the painting was recognized for what it was, as no specimens or skins of this bird had ever been collected. Thus again, only by the sheerest chance was solid evidence of a bird’s existence discovered.

The Lord Howe Pigeon was just one of an amazing variety of indigeneous birds that lived on an island only 11km (7 miles) long and 1.5km (1 mile) wide. Early European observers never seemed to tire of their own amazement at the tameness of birds who had never before seen men. Yet their reactions to such unwariness were always predictably and brutally the same.

In the year 1788, the Surgeon Arthur Bowes of the Lady Penrhyn, on landing on Lord Howe Island, wrote: ‘The sport we had in knocking down birds was very great . . . the Pidgeons were the largest I ever saw . . . When I was in the woods among the birds I could not help picturing to myself the Golden Age as described by Ovid – to see the Fowls or Coots some white, some blue and white, others all blue with large red bills . . . together with a curious brown bird about the size of the Land Reel in England walking totally fearless and unconcerned in all parts around us so that we had nothing more to do than stand still a minute or two and knock down as many as we pleased . . . if you missed them they would never run away . . . The Pidgeons also were as tame as those already described and would sit upon the branches of the trees till you might go and take them off with your hands . . . many hundreds of all sorts mentiond above together with Parrots and Parroquets, Magpies, and other Birds were caught and carried on board our ship with the Charlotte.’

The captain of the Charlotte, Thomas Gilbert, wrote about the birds in his diary on the same day: ‘Several of these I knocked down, and their legs being broken, I placed them near me as I sat under a tree. The pain they suffered caused them to make a doleful cry which brought five or siz dozen of the same kind to them and by that means I was able to take nearly the whole of them.’

The toll of the European ships on the birds of the island was such that a Dr Foulis who lived on the island from 1844 to 1847, when the human population was still only 16, wrote: ‘There are but few birds that belong to the island, the only valuable kind being a large blue pigeon . . .’ It is no wonder that by 1853, at least, the Lord Howe Pigeon was no more. Surgeon Bowes’ ‘Golden Age’ was over.

Traditionally the Dove is the sign of peace, innocence, and gentleness; it is also symbolic of the presence of the Holy Spirit. According to medieval chronicles: ‘The Dove is a simple fowl free from gall, and it asks for love with its eye.’ For at least five thousand years Men have been keeping doves, and have loved them for their peaceful nature. Doves and pigeons feed from the hand of Man and have even adapted to ‘cliff-dwelling’ in the world’s largest cities on man-made towers and buildings. Adaptation and tameness has frequently been their salvation.

It is strange, therefore, that these characteristics of fearlessness and naivety, when encountered by European men in the wild, have invariably been interpreted as stupidity. So we find that the characteristics which in one context are seen as praiseworthy, and in another damning, have resulted in the extinction of not less than one dozen species of ‘gentle doves’.