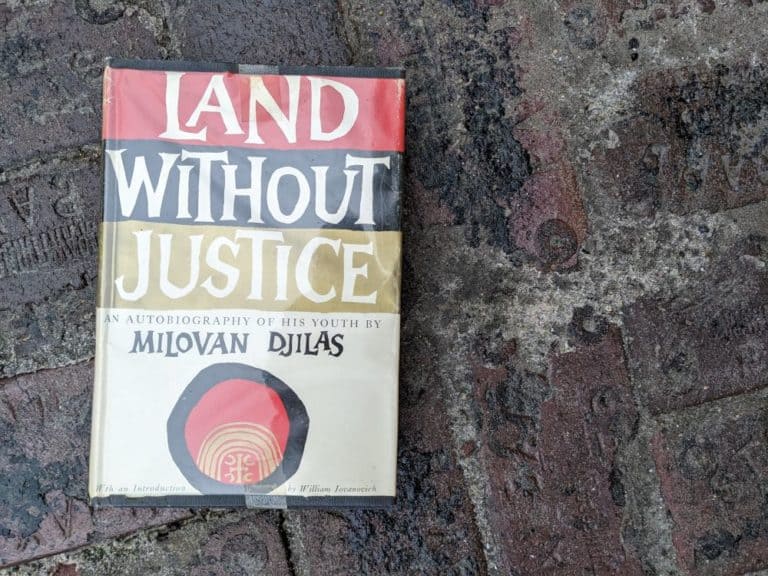

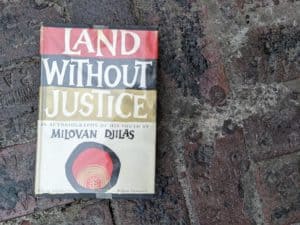

Last October on our trip to Kansas City to see the Bills play the Chiefs, I was lucky to find Land Without Justice at Steel’s Used Books. Mr. Steel sold us a goodly pile of interesting books at a reasonable price. We were sorry to hear that in the years prior, he’d been forced to relocate, substantially downsizing his stock. Thanks for the good books, Mr. Steel. To us your small store was a diamond!

“Reading can take you places you’ve never been before.” That trivial aphorism started to seem insightful while I read Land Without Justice. The book begins with the story of Djilas’ ancestors. He traces the deaths of several generations of family members through feuds with other clans and with the authorities. Some cultures keep family ancestry records going back thousands of years; or engage in ancestor worship; but the grim genealogy provided by Djilas put Montenegrins in a class all their own. To me they seemed as remote as Martians in a science fiction.

In the far-off land of Montenegro, there once was a prince-bishop poet. Years after his death the peasants still kept his most famous work committed, line by line, to memory. Cold clear streams gushed over the jagged mountains. Peasants tended herds of skinny cattle. Brave men fought the ever-encroaching Turks. Later they fought the Austrians. Guerrillas hid in the woods. Cities grew and changed. Strange ideologies took hold, only to be stamped out again when regimes changed. These things and more I learned from Djilas’ book. But I am no student of history; nor of politics; nor of geography.

To me, the sweetness of Land Without Justice lies solely in Djilas’ abilities as a narrator. At its core, the book is quite a simple autobiography. Djilas merely attempts to describe each important person Djilas knew in his youth, and tell that person’s story. All are worthy of Djilas’ attentive pen: women, children, Spotty the bull, and every one of his grade- and high-school teachers. Djilas possesses a spectacular memory, and his descriptive prowess is something like Dostoevsky’s. He really makes people come alive!

Stanojka lived long. But always, her whole life through, her head trembled markedly. Though well built and sturdy of frame, she remained somewhat lost from that night on, both in her speech and in her mind. Her brothers and mother, as well as her own children, later, and everyone else knew of the shock she had suffered. And she, too, knew. But she endured her misfortune calmly and patiently, as though she had explained it all to herself: It had to be so; she did what a woman was obliged to do for her kin. She was neither proud for retrieving her father’s head from the enemy and from the water that night nor ashamed for becoming dazed and unsettled the rest of her life. She was at peace with herself and with life, seeking nothing, clinging to her brothers and their children, and to her only son. Her brothers took poor care of her, though she was impoverished and without a roof or a foot of land, not so much because of stinginess, but more because they believed that, unsound and withdrawn as she was, she did not need anything, that she was incapable of wanting. She was as delighted as a child over the smallest gift, guarding it jealously however worthless it might be. Life did not shower her with bounties.

Late at night, when all would be asleep, she would get up, stir the embers of the fire on the hearth, and stare bluntly at the dancing flames. Her sturdy feet, cracked and as broad as hoofs—for she constantly went barefoot—were turned soles to the fire, and the hard, gnarled fingers of her hands were clasped about her knees. Hunched up thus, she could sit for hours, until some sound or the dawn startled her. Sometimes, sitting thus, she would hunch over even more and begin to cry, not in any usual way, but without a sound, without a movement, only the tears streaming from large green eyes down a face cracked by sun and toil and plowed over by misfortune, a rock beaten by wind and rain. When she found herself alone in the mountain where she thought no one could hear her, she would wail aloud.

Through these intimate, sensitive descriptions, Djilas earns the reader’s trust. There can be little doubt as to his competence as a historian, storyteller, and likeable guy, I figured. I resolved to put this book up on my shelf with Celine and Limonov. Then I saw Underground (1995 film). I couldn’t help but notice that Marko, the guy who imprisons everybody in the basement, happens to be portrayed as “Tito’s right-hand man” and some kind of a writer, to boot. Was this character meant to satirize Djilas, who had been Tito’s right-hand man? It was a puzzle to ponder while I finished the last few chapters of Land Without Justice. Unless I find a copy of the second part of Djilas’ autobiography in some other used bookstore, I guess I’ll never get to know for sure.

I didn’t have fun watching Underground, but in the end I understood it to have dredged up and poked fun at things that happened and ways people behaved during the long, war-torn history of Yugoslavia. The movie brewed a vile cauldron of the times. Into the pot went history, conspiracy, music, love, rumor, pain, fear, bombs, guns, an entire zoo full of animals. The stench of the times wafts out of the television and stings the eyes. One idea to which Djilas frequently returns in Land Without Justice is that men cannot be separated from the stew in which they live.

Attempting to find their bearings and to conquer the new times, these men seemed only to become all the more lost, more violent, and more embittered. If the times, with their sudden convulsions—their wars and destruction and outmoded ways of life—were to blame, could not these people have prevailed? Are men doomed to become the slaves of the times in which they live, even when, after irrepressible and tireless effort, they have climbed so high as to become masters of the times?

What are my times? The era of the mobile device, of non-stop propaganda. The era of genetically modified organisms. The era of inflammation.

Review: Land Without Justice by Milovan Djilas

Milovan Djilas' 'Autobiography of His Youth' comes highly recommended.

5